11/23/05 Today, is Thanksgiving Day. There are only four days left of the Wisconsin deer hunting season. I just finished up Tales of Adam by Daniel Quinn. This is another masterpiece by DQ. I really like the fact that I got the chance to read ToA during deer hunting season.

I wrote a review of it for Amazon.com. I don't know if I'm going to post it yet. Here it is:

More Important than the Bible

After reading the final pages of Tales of Adam, one word comes to mind, and that is: wisdom. This book may be small, but it is packed full of important teachings. Teachings I wish would’ve come across a lot earlier in life, teachings that make sense, teachings that have stood the test of time, teachings that need to be learned by the members of the most destructive and suicidal culture ever to exist, teachings that are there for all of life to follow, not just man. Teachings that make me feel like I have purpose, teachings that make me feel like I belong.

This book, I feel, is as important as the rest of Daniel Quinn’s work. I feel fortunate to have read Tales of Adam. It has made me a better person.

books Religion Hunting Wisconsin Sustainability

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

The Snow is Falling!

It's about 8:30 PM here in Northern Wisconsin. I just stepped outside and noticed the ground was white with snow. That'd be the first snowfall for this winter season, and many more to go!

I've spent the last two hours on-line reading articles on subjects ranging anywhere from cancer, peak oil, to learning how to bond with the land. The three articles I read by Micheal Ventura are a good read. They mostly discuss what we are going to be facing in the future as far as Peak Oil is concerned.

The article about cancer was titled: Why We Can't Prevent Cancer in Rachel's Democracy and Health News. It was sobering, to say the least. Defintely, check it out if you care about your body.

The article by Jeanette Armstrong titled: I Stand With You Against the Disorder was about learning how to face crisis as a community. It was wise, and therefore a breath of fresh air for me. It was posted over at IshCon. Jeanette comes from a very wise cultural upbringing. I was first introduced to her words through Derrick Jensen's "A Language Older Than Words."

I think it is time to step away from the screen to go out and enjoy the snowfall!!!

Health Peak Environment Sustainability Books Wisconsin

I've spent the last two hours on-line reading articles on subjects ranging anywhere from cancer, peak oil, to learning how to bond with the land. The three articles I read by Micheal Ventura are a good read. They mostly discuss what we are going to be facing in the future as far as Peak Oil is concerned.

The article about cancer was titled: Why We Can't Prevent Cancer in Rachel's Democracy and Health News. It was sobering, to say the least. Defintely, check it out if you care about your body.

The article by Jeanette Armstrong titled: I Stand With You Against the Disorder was about learning how to face crisis as a community. It was wise, and therefore a breath of fresh air for me. It was posted over at IshCon. Jeanette comes from a very wise cultural upbringing. I was first introduced to her words through Derrick Jensen's "A Language Older Than Words."

I think it is time to step away from the screen to go out and enjoy the snowfall!!!

Health Peak Environment Sustainability Books Wisconsin

Monday, November 14, 2005

Peak Oil on My Mind

This morning, I’ve got Peak Oil on my mind. My thoughts have been inspired from an email a friend of mine sent me regarding a paper that was presented at a Reception with Their Royal Highnesses The Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall, and the California Leaders Round Table Dialogue on Peak Oil, Climate Change and Business Action by Richard Heinberg. After I read the article, a few statements from it come to mind. The first one points out how much we depend on fossil fuels to do our work.

He than goes on to say.

Like Heinberg alludes to in the above statement, it can’t be argued that eventually the global production of oil is going to peak. It’s a finite resource, so it only stands to reason. The next question is are we going to be prepared for this when it happens (if it hasn’t happened already). One of the measures Heinberg is suggesting for us to take is that we need to reduce our dependence on this stuff ASAP. Another thing he suggests is a global Oil Depletion Protocol.

We’ll see if this global Oil Depletion Protocol will become policy for most nations. As of right now, I would guess the United States would be the last to adopt this as policy. But, we’ll see what happens.

Peak Oil Politics United

“Only 150 years ago, 85% of all work being accomplished in the US economy was done by muscle power-most of that by animal muscle, about a quarter of it by human muscle. Today, that percentage is effectively zero; virtually all of the physical work supporting our economy is done by fuel-fed machines. What caused this transformation? Quite simply, it was oil's comparative cheapness and versatility. Perhaps you have had the experience of running out of gas and having to push your car a few feet to get it off the road. That's hard work. Now imagine pushing your car 20 or 30 miles. That is the service performed for us by a single gallon of gasoline, for which we currently pay $2.65. That gallon of fuel is the energy equivalent of roughly six weeks of hard human labor.

”It was inevitable that we would become addicted to this stuff, once we had developed a few tools for using it and for extracting it. Today petroleum provides 97 percent of our transportation fuel, and is also a feedstock for chemicals and plastics.

”It is no exaggeration to say that we live in a world that runs on oil.” Richard Heinberg

He than goes on to say.

“However, oil is a finite resource. Therefore the peaking and decline of world oil production are inevitable events-and on that there is scarcely any debate; only the timing is uncertain. Forecast dates for the peak range from this year to 2035.” Heinberg

Like Heinberg alludes to in the above statement, it can’t be argued that eventually the global production of oil is going to peak. It’s a finite resource, so it only stands to reason. The next question is are we going to be prepared for this when it happens (if it hasn’t happened already). One of the measures Heinberg is suggesting for us to take is that we need to reduce our dependence on this stuff ASAP. Another thing he suggests is a global Oil Depletion Protocol.

“A global Oil Depletion Protocol would reduce price volatility and competition for remaining supplies, while encouraging nations to move quickly to wean themselves from petroleum. In essence, the Protocol would be an agreement whereby producing nations would plan to produce less oil with each passing year (and that will not be so difficult, because few are still capable of maintaining their current rates in any case); and importing nations would agree to import less each year. That may seem a bitter pill to swallow.

”However, without a Protocol-essentially a system for global oil rationing-we will see extremely volatile prices that will undermine the economies of all nations, and all industries and businesses.

”We will also see increasing international competition for oil likely leading to conflict; and if a general oil war were to break out, everyone would lose. Given the alternatives, the Protocol clearly seems preferable.

”National governments, local municipalities, corporations, and private individuals will all need to contribute to the effort to wean ourselves from oil, and effort that must quickly expand to include a reduction in dependence on other fossil fuels as well. All of this will constitute an immense challenge for our species in the coming century. We will meet that challenge successfully only if we begin immediately.” R. Heinberg

We’ll see if this global Oil Depletion Protocol will become policy for most nations. As of right now, I would guess the United States would be the last to adopt this as policy. But, we’ll see what happens.

Peak Oil Politics United

Saturday, November 12, 2005

Republicans Concerned about Peak Oil

From what I got out of this article, it looks to me like the political right in this country is starting to become a little concerned about Peak Oil. They're actually talking about increasing the number of hybrid electric vehicles sold in America.

When talking about increasing the number of hybrid electric vehicles, I can't help but think about what Jason Godesky wrote in his "Thesis#16:Technology cannot stop collapse" over at Anthropik. It has to do with Jevons Paradox."William Stanley Jevons is a seminal figure in economics.

It seems a civilizational collapse is inevitable, and for all we know civilization is collapsing. It is in our best interest, I think, to start preparing for the inevitable collapse instead of trying to prolong the life of civilization by improving our technologies. I think, SOME of the answers may be found here.

Books Politics Religous Civilization Collapse Peak

"Leading the energy security front is a coalition called Set America Free. Led by the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, Set America Free's members include former Republican presidential candidate and "family values" activist Gary Bauer; powerful neoconservative security hawks Frank Gaffney, Daniel Pipes and former CIA director Jim Woolsey; and National Resources Defense Council's (NRDC) Deron Lovaas along with the Apollo Alliance's Bracken Hendricks.

"In an open letter signed by its members, Set America Free calls for an end to oil dependency for security purposes and makes the centerpiece of its blueprint a call to improve fuel economy rates for automobiles, diversify auto fuels and increase the number of hybrid electric vehicles sold in America."

When talking about increasing the number of hybrid electric vehicles, I can't help but think about what Jason Godesky wrote in his "Thesis#16:Technology cannot stop collapse" over at Anthropik. It has to do with Jevons Paradox."William Stanley Jevons is a seminal figure in economics.

He helped formulate the very theory of marginal returns which, as we saw in thesis #14, governs complexity in general, and technological innovation specifically. In his 1865 book, The Coal Question, Jevons noted that the consumption of coal in England soared after James Watt introduced his steam engine. Steam engines had been used as toys as far back as ancient Greece, and Thomas Newcomen's earlier design was suitable for industrial use. Watt's invention merely made more efficient use of coal, compared to Newcomen's. This made the engine more economical, and so, touched off the Industrial Revolution--and in so doing, created the very same modern, unprecedented attitudes towards technology and invention that are now presented as hope against collapse. In the book, Jevons formulated a principle now known as "Jevons Paradox." It is not a paradox in the logical sense, but it is certainly counterintuitive. Jevons Paradox states that any technology which allows for the more efficient use of a given resource will result in greater use of that resource, not less. By increasing the efficiency of a resource's use, the marginal utility of that resource is increased more than enough to compensate for the fall. This is why innovations in computer technology have made for longer working hours, as employers expect that an employee with a technology that cuts his work in half can do three times more work. This is why more fuel-efficient vehicles have resulted in longer commutes, and the suburban sprawl that creates an automotive-centric culture, with overall higher petroleum use.

Most of the technologies offered as solutions to collapse expect Jevons Paradox not to hold. They recognize the crisis we face with deplenishing resources, but hope to solve that problem by making the use of that technology more efficient. Jevons Paradox illustrates precisely what the unintended consequence of such a technology will be--in these cases, precisely the opposite of the intended effect. Any technology that aims to save our resources by making more efficient use of them can only result in depleting those resources even more quickly.

The best hope technology can offer for staving off collapse is to tap a new energy subsidy, just as the Industrial Revolution tapped our current fossil fuel subsidy. For instance, the energy we currently use in petroleum could be matched by covering 1% of the United States' land area in photovoltaic cells. However, the hope that human population will simply "level off" due to modernization is in vain (see thesis #4); human population is a function of food supply, and population will always rise to the energy level available. The shift to photovoltaics, like the shift to fossil fuels, is merely an invitation to continued growth--another "win" in the "Food Race." If our energy needs can be met by covering just 1% of the United States with photovoltaic cells, why not cover 2% and double our energy? Of course, then our population will double, and we'll need to expand again.

Such technological advances can postpone collapse, but they cannot stop it. However, there is also a cost associated with such postponements: each one makes collapse, when it eventually does happen, exponentially more destructive."

It seems a civilizational collapse is inevitable, and for all we know civilization is collapsing. It is in our best interest, I think, to start preparing for the inevitable collapse instead of trying to prolong the life of civilization by improving our technologies. I think, SOME of the answers may be found here.

Books Politics Religous Civilization Collapse Peak

Pondering Slavery

It’s Saturday morning; I’m reading A Man Without a Country by Kurt Vonnegut, again. There is a passage in their that has got me thinking about Derrick Jensen, relationships, slavery and civilization. The passage reads:

My knee jerk reaction after reading this was one of surprise. Slave owners become suicidal and suffer from depression? Aren’t we all taught in this culture that we must try to get rich and have a lot of people working for us? Isn’t this what the immortal Henry Ford did? And how about Bill Gates? I Bet you there is a few of us who wouldn’t mind being as well off as Bill Gates is, or as Henry F. once was? But what about the relationships, these cultural demigods we're supposed to envy, share?

When it comes to a voice of sanity regarding relationships, I have to turn to Derrick Jensen. In Walking On Water: Reading, Writing, and Revolution he wrote:

“A human being is not simply an ego structure in a sack of skin. Human beings, and this is true for all beings, are the relationships they share. My health—emotional, physical, moral—is inextricably intertwined with the quality of these relationships, whether I acknowledge the relationships or not. If the relationships are impoverished, or if I systematically eradicate those beings with whom I pretend I do not have relationships, I am so much smaller, so much weaker. These statements are as true physically as they are emotionally and spiritually.”

It’s no wonder the suicide rate per capita among white slave owners was higher than that of the slaves they perceived as owning.

This leads me to ask myself, “how do I benefit from slavery?” Of course we all know that slavery didn’t disappear after the Civil War between the North and the South of the United States. Don’t we? What about this thing we call wage slavery? You know, where you go to work for Six Dollars an Hour while the CEO of the corporation your working for makes about 400 times more than you. Funny thing, I didn’t start to understand what wage slavery was until I was in my mid-twenties. I blame part of this on my schooling, but that’s a whole other story.

So…I’m civilized. Which means I depend on civilization to survive. This has got me thinking about how much I depend on slavery to maintain my personal standard of living. This leads me to pg. 59 of Jensen’s “The Culture of Make Believe.” He quotes Fredrich Engels as saying “It was slavery that first made possible the division labour between agriculture and industry on a considerable scale, and along with this, the flower of the ancient world, Hellenism. Without slavery, no Greek state, no Greek art and science; without slavery, no Roman Empire. But without Hellenism and the Roman Empire as the base, also no modern Europe. We should never forget that our whole economic, political and intellectual development has as its presupposition a state of things in which slavery was as necessary as it is universally recognized.”

I bet you anyone reading this has something they can look at right now that was made using slave labor. My sweatshirt is made in Myanmar. I wonder how much the workers that made this were paid? I ask myself why wasn’t it made in the United States? Is it cheaper for the owners of RESERVOIR clothing to have it made in Myanmar? Jensen goes on to say “ ‘Servitude’ Harper noted, ‘ is the condition of civilization.’ It seems pretty clear, then, that if you want civilization, you’ve got to have slavery, or at least servitude. To undo slavery—if this argument holds—would be to undo the civilization we—at least those of us who might be considered slaveholders—all enjoy.”

But do they enjoy it? Do most of us (who are civilized) enjoy the benefits of servitude and slavery? I think I read somewhere that the suicide rate among teenagers in the United States has increased almost 400% in the last fifty years. Wouldn’t life be better if there was no such thing as slavery? Wouldn’t life be better if there was no such thing as civilization? Why aren’t we talking about this more…? Books civilization Slavery Jobs Mental Schooling

“The wonderful writer Albert Murray, who is a jazz historian and a friend of mine among other things, told me that during the era of slavery in this country --an atrocity from which we can never fully recover—the suicide rate per capita among slave owners was much higher than the suicide rage among slaves.

“Murray says he thinks this was because slaves had a way of dealing with depression, which their white owners did not: They could shoo away Old Man Suicide by playing and singing the Blues.”

My knee jerk reaction after reading this was one of surprise. Slave owners become suicidal and suffer from depression? Aren’t we all taught in this culture that we must try to get rich and have a lot of people working for us? Isn’t this what the immortal Henry Ford did? And how about Bill Gates? I Bet you there is a few of us who wouldn’t mind being as well off as Bill Gates is, or as Henry F. once was? But what about the relationships, these cultural demigods we're supposed to envy, share?

When it comes to a voice of sanity regarding relationships, I have to turn to Derrick Jensen. In Walking On Water: Reading, Writing, and Revolution he wrote:

“A human being is not simply an ego structure in a sack of skin. Human beings, and this is true for all beings, are the relationships they share. My health—emotional, physical, moral—is inextricably intertwined with the quality of these relationships, whether I acknowledge the relationships or not. If the relationships are impoverished, or if I systematically eradicate those beings with whom I pretend I do not have relationships, I am so much smaller, so much weaker. These statements are as true physically as they are emotionally and spiritually.”

It’s no wonder the suicide rate per capita among white slave owners was higher than that of the slaves they perceived as owning.

This leads me to ask myself, “how do I benefit from slavery?” Of course we all know that slavery didn’t disappear after the Civil War between the North and the South of the United States. Don’t we? What about this thing we call wage slavery? You know, where you go to work for Six Dollars an Hour while the CEO of the corporation your working for makes about 400 times more than you. Funny thing, I didn’t start to understand what wage slavery was until I was in my mid-twenties. I blame part of this on my schooling, but that’s a whole other story.

So…I’m civilized. Which means I depend on civilization to survive. This has got me thinking about how much I depend on slavery to maintain my personal standard of living. This leads me to pg. 59 of Jensen’s “The Culture of Make Believe.” He quotes Fredrich Engels as saying “It was slavery that first made possible the division labour between agriculture and industry on a considerable scale, and along with this, the flower of the ancient world, Hellenism. Without slavery, no Greek state, no Greek art and science; without slavery, no Roman Empire. But without Hellenism and the Roman Empire as the base, also no modern Europe. We should never forget that our whole economic, political and intellectual development has as its presupposition a state of things in which slavery was as necessary as it is universally recognized.”

I bet you anyone reading this has something they can look at right now that was made using slave labor. My sweatshirt is made in Myanmar. I wonder how much the workers that made this were paid? I ask myself why wasn’t it made in the United States? Is it cheaper for the owners of RESERVOIR clothing to have it made in Myanmar? Jensen goes on to say “ ‘Servitude’ Harper noted, ‘ is the condition of civilization.’ It seems pretty clear, then, that if you want civilization, you’ve got to have slavery, or at least servitude. To undo slavery—if this argument holds—would be to undo the civilization we—at least those of us who might be considered slaveholders—all enjoy.”

But do they enjoy it? Do most of us (who are civilized) enjoy the benefits of servitude and slavery? I think I read somewhere that the suicide rate among teenagers in the United States has increased almost 400% in the last fifty years. Wouldn’t life be better if there was no such thing as slavery? Wouldn’t life be better if there was no such thing as civilization? Why aren’t we talking about this more…? Books civilization Slavery Jobs Mental Schooling

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Addicts in Denial

November 10. After starting a fire to warm up the house this morning, I had the luxury to sit down for a few minutes and read a few chapters out of Kurt Vonnegut’s new book "A Man Without a Country".

This passage by Vonnegut rings true when it comes to discussing fossil fuels and the end of civilization:

There it is. I mean come on, like the United States Government is really trying to spread peace to the Middle East. They want the oil underneath the Iraqi’s soil. How did that saying go? “How did our oil get underneath your soil?” And we all know how much our lives are going to drastically change when we can’t afford this stuff anymore. We are addicted to fossil fuels, there is just no two ways about it.

Talking about our addiction to fossil fuels. This thing called, “Jevons Paradox” is startling. I first learned about it in reading a post titled “Thesis#16: Technology cannot stop collapse" over at Anthropik.

Here is what Jason Godesky had to say about “Jevons Paradox”:

This really makes sense to me. Essentially, what I get from this is, that when we are able to improve a technology to the point where it makes more efficient use of a resource we will use that resource up faster. So Hybrid cars sound like the way to go (I wish I could afford one) if we want to use less oil, but according to Jevon the oil will be used up even quicker.

We really need to get "Beyond Civilization" as soon as possible.

collapse peak Technology Cars Addiction Civilization Jevons Books

This passage by Vonnegut rings true when it comes to discussing fossil fuels and the end of civilization:

“When you got here, even when I got here, the industrialized world was already hopelessly hooked on fossil fuels, and very soon now there won’t be any left. Cold Turkey.

“Can I tell you the truth? I mean this isn’t the TV news is it? Here’s what I think the truth is: We are all addicts of fossil fuels in a state of denial. And like so many addicts about to face cold turkey, our leaders are now committing violent crimes to get what little is left of what we’re hooked on.”

There it is. I mean come on, like the United States Government is really trying to spread peace to the Middle East. They want the oil underneath the Iraqi’s soil. How did that saying go? “How did our oil get underneath your soil?” And we all know how much our lives are going to drastically change when we can’t afford this stuff anymore. We are addicted to fossil fuels, there is just no two ways about it.

Talking about our addiction to fossil fuels. This thing called, “Jevons Paradox” is startling. I first learned about it in reading a post titled “Thesis#16: Technology cannot stop collapse" over at Anthropik.

Here is what Jason Godesky had to say about “Jevons Paradox”:

“William Stanley Jevons is a seminal figure in economics. He helped formulate the very theory of marginal returns which, as we saw in thesis #14, governs complexity in general, and technological innovation specifically. In his 1865 book, The Coal Question, Jevons noted that the consumption of coal in England soared after James Watt introduced his steam engine. Steam engines had been used as toys as far back as ancient Greece, and Thomas Newcomen's earlier design was suitable for industrial use. Watt's invention merely made more efficient use of coal, compared to Newcomen's. This made the engine more economical, and so, touched off the Industrial Revolution--and in so doing, created the very same modern, unprecedented attitudes towards technology and invention that are now presented as hope against collapse. In the book, Jevons formulated a principle now known as "Jevons Paradox." It is not a paradox in the logical sense, but it is certainly counterintuitive. Jevons Paradox states that any technology which allows for the more efficient use of a given resource will result in greater use of that resource, not less. By increasing the efficiency of a resource's use, the marginal utility of that resource is increased more than enough to compensate for the fall. This is why innovations in computer technology have made for longer working hours, as employers expect that an employee with a technology that cuts his work in half can do three times more work. This is why more fuel-efficient vehicles have resulted in longer commutes, and the suburban sprawl that creates an automotive-centric culture, with overall higher petroleum use.

“Most of the technologies offered as solutions to collapse expect Jevons Paradox not to hold. They recognize the crisis we face with deplenishing resources, but hope to solve that problem by making the use of that technology more efficient. Jevons Paradox illustrates precisely what the unintended consequence of such a technology will be--in these cases, precisely the opposite of the intended effect. Any technology that aims to save our resources by making more efficient use of them can only result in depleting those resources even more quickly.”

This really makes sense to me. Essentially, what I get from this is, that when we are able to improve a technology to the point where it makes more efficient use of a resource we will use that resource up faster. So Hybrid cars sound like the way to go (I wish I could afford one) if we want to use less oil, but according to Jevon the oil will be used up even quicker.

We really need to get "Beyond Civilization" as soon as possible.

collapse peak Technology Cars Addiction Civilization Jevons Books

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

The Fruits of our Labor

Back in 1999, after discussing where we go after we die, a friend of mine suggested that I read Ishmael by Daniel Quinn. In a matter of days I finished. That was pretty good considering that up until that point in my life I could count the number of books I’ve read on one hand. It didn’t take long after that and I devoured everything Quinn had written. From that point on I went from a person with little or no interest in books to someone that would be content reading 4 to 5 hours a day. Quite literally the library could be my second place of residence.

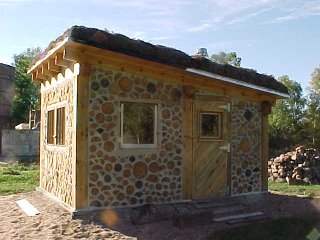

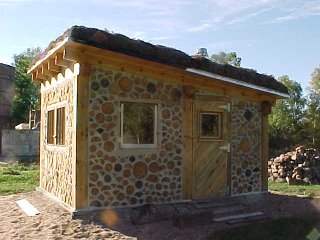

One of the books I ran across on my reading journey was a book about the cordwood building method: The Sauna by Rob Roy. After reading that I knew I had to get out of debt. Since my only debt at that time was a mortgage I had taken out to build my conventional stick frame house, I knew the next step I would have to take would be to sell it. My plan than was to use the equity I had built up to pay for the land and materials for another house building venture. And cordwood seemed like the way to go. Plus, I had spent a lot of time in the woods as a logger, so I knew a little bit about the woods.

A few years later, I managed to sell the house and 20 acres. I then went with my plan of using the equity to pay for the land that I would eventually build the cordwood building on. Luckily, there was 32 acres for sale within a few miles from the house I had just sold. It was priced reasonable, so I bought it. Now it was time to experiment with cordwood.

After reading various people’s experiences with the cordwood building method, we (by this time I had met Annie) figured that a practice building would be the way to start out. Again, Rob Roy’s Sauna book was useful. The 10’ x14’8” rectilinear post and beam sauna design he illustrates and writes about seemed do-able.

And, as you can see from the pictures, approximately five years after I opened up The Sauna book, we’ve got a good start on our on-going process of building with cordwood. We plan on starting our 41ft. diameter cordwood round house next spring.

If you’re interested in connecting up with other experienced cordwood builders, I highly recommend checking out Daycreek. Everyone there has been extremely helpful to us during this process. And another invaluable resource regarding cordwood is Rob Roy’s website.

Alternative construction Projects Home Cordwood

Masonry

wood Wisconsin design Books

One of the books I ran across on my reading journey was a book about the cordwood building method: The Sauna by Rob Roy. After reading that I knew I had to get out of debt. Since my only debt at that time was a mortgage I had taken out to build my conventional stick frame house, I knew the next step I would have to take would be to sell it. My plan than was to use the equity I had built up to pay for the land and materials for another house building venture. And cordwood seemed like the way to go. Plus, I had spent a lot of time in the woods as a logger, so I knew a little bit about the woods.

A few years later, I managed to sell the house and 20 acres. I then went with my plan of using the equity to pay for the land that I would eventually build the cordwood building on. Luckily, there was 32 acres for sale within a few miles from the house I had just sold. It was priced reasonable, so I bought it. Now it was time to experiment with cordwood.

After reading various people’s experiences with the cordwood building method, we (by this time I had met Annie) figured that a practice building would be the way to start out. Again, Rob Roy’s Sauna book was useful. The 10’ x14’8” rectilinear post and beam sauna design he illustrates and writes about seemed do-able.

And, as you can see from the pictures, approximately five years after I opened up The Sauna book, we’ve got a good start on our on-going process of building with cordwood. We plan on starting our 41ft. diameter cordwood round house next spring.

If you’re interested in connecting up with other experienced cordwood builders, I highly recommend checking out Daycreek. Everyone there has been extremely helpful to us during this process. And another invaluable resource regarding cordwood is Rob Roy’s website.

Alternative construction Projects Home Cordwood

Masonry

wood Wisconsin design Books

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Imprisoning the Sun God

Yesterday, out of no plan of my own, I ended up in the soft chair at my local library reading the The Man Who Grew Young by Daniel Quinn. I’ve read it before. In fact, I use to own it. But as with any good book that you loan out, it seems like you usually have a hard time getting it back.

Less than 24 hours later, I can truly say it was a pleasure to read TMWGY, again. As messed up as everything is in the world, for a few moments TMWGY gives you this feeling that everything is going to be all right.

What I’ve been thinking about since finishing TMWGY was an exchange between Adam (The books main character) and Merlin (A wizard that Adam runs into on his journey through Europe) about Stonehenge.

I should remind the reader that time is no longer moving forward (as we think of it to be) in TMWGY, its now moving backwards.

Now I’m rubbing my chin. I don’t know much about Stonehenge. I’ve only seen images of it on television, and in books, as I was growing up. But Quinn is trying to point out something that seems blatantly obvious. Is he saying that since they learned how to follow the patterns of the sun by using the structure of Stonehenge they imprisoned themselves to this structure? And if they suddenly became free from their enslavement,what other options are there?

And something else that has ran across my mind since reading this. What about the generations of workers who broke their backs to build this thing? Did they think they were imprisoning the sun god? They almost had to think that this is what people just “did”. I’m sure they didn’t give it any more thought than we do when we get up in the morning to go off to do our jobs. And most people who go off to jobs they hate have to be thinking to themselves there has to be a better way. We're the people that built Stonehenge thinking this too?

The Man Who Grew Young has definitely got me thinking.

Books God Life Faith History Fiction Stonehenge Astronomy Europe

Less than 24 hours later, I can truly say it was a pleasure to read TMWGY, again. As messed up as everything is in the world, for a few moments TMWGY gives you this feeling that everything is going to be all right.

What I’ve been thinking about since finishing TMWGY was an exchange between Adam (The books main character) and Merlin (A wizard that Adam runs into on his journey through Europe) about Stonehenge.

I should remind the reader that time is no longer moving forward (as we think of it to be) in TMWGY, its now moving backwards.

As they are walking to the river, Adam asks. “Why do you think they dismantled Stonehenge?”

Merlin answers. “It was time to release the prisoner.”

“I don’t know what that means”

“Do you know what a henge is?”

“I don’t know…something like a hinge”

Merlin responds. “Close, but no cigar. It’s like the word Girt. Do you know what an expression like stone-girt might mean?”

“Stone-girt…something like ‘held in by stone?’”

“That’s right. Stonehenge means ‘stone-hung.’”

“Stone-hung? I don’t get it.” Adams confused.

Not many people did in your ancient times. They thought it had something to do with hanging stones. Did you see any hanging stones there?”

Adam responds. “No, I didn’t”

A few moments later Merlin asks. “ So, what do you suppose was hung by stone at Stonehenge?”

“ I have no idea.”

“Yes, you do. And when I tell you, you’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s very obvious.”

“Try me.”

A god was hung on the stones of Stonehenge.”

Looking perplexed, Adam responds with, “Huh!”

“Two hundred generations of people labored to dismantle Stonehenge, dragging thirty-ton stones to quarries dozens of miles away. Why?”

“Didn’t they use it as a calendar to regulate the planting of crops?”

That was the God’s work. He was imprisoned to perform that service.” Merlin replies.

Adams baffled. “ I don’t get it.”

Pacing his cell, the god showed them exactly when to plant year after year.”

“What god was it?”

Merlin is agitated now. “Oh use a little imagination, for gods sake! Look…

Merlin and Adam lean over a drawing of Stonehenge that Merlin etched in to the dirt with his walking stick. Pointing at the drawing, Merlin calmly goes on. “This was the stronghold. You see. The Bastille. The Bluestone Circle, another century of work…the Sarsen Circle, a century of work all by itself…and this line here, this marked midsummer sunset.

“But that’s just the beginning. There was the midwinter sunset, the solstices, the equinoxes…all the days, all the moments.

“Does this give you any idea about the prisoner?”

“I’m not sure. The sun?” Adam asks.

“Of course! At Stonehenge, the sun was like a slave with one foot nailed to the floor. It was compelled to circle Stonehenge every year, in and out, decade after decade, century after century.”

“But that doesn’t explain why they got rid of it.”

“They got rid of it because they were sick of it! Every prison creates two sets of captives—inmates and warders, who are as firmly shackled to the prison as the inmates.

“The sun was their captive, but they were its captive as well, and they got tired of it.”

Rubbing his chin with a contemplative look on his face, Adam stares at the drawing etched in the dirt.

Now I’m rubbing my chin. I don’t know much about Stonehenge. I’ve only seen images of it on television, and in books, as I was growing up. But Quinn is trying to point out something that seems blatantly obvious. Is he saying that since they learned how to follow the patterns of the sun by using the structure of Stonehenge they imprisoned themselves to this structure? And if they suddenly became free from their enslavement,what other options are there?

And something else that has ran across my mind since reading this. What about the generations of workers who broke their backs to build this thing? Did they think they were imprisoning the sun god? They almost had to think that this is what people just “did”. I’m sure they didn’t give it any more thought than we do when we get up in the morning to go off to do our jobs. And most people who go off to jobs they hate have to be thinking to themselves there has to be a better way. We're the people that built Stonehenge thinking this too?

The Man Who Grew Young has definitely got me thinking.

Books God Life Faith History Fiction Stonehenge Astronomy Europe

Sunday, November 06, 2005

Putting Food on the Table

Since I've first read Ishmael , and the rest of Daniel Quinn's work, this quote from Beyond Civilization has stuck in my mind:

"Making food a commodity to be owned was one of the great innovations of our culture. No other culture in history has ever put food under lock and key--and putting it there is the cornerstone of our economy, for if the food wasn't under lock and key, who would work?"

He than goes on to say...

"People don't plant crops because it's less work, they plant crops because they want to settle down and live in one place. An area that is only foraged doesn't yield enough human food to sustain a permanant settlement. To build a village, you must grow crops--and this is what most aboriginal villagers grow: some crops. They don't grow all their food. They don't need to.

"Once you begin turning all the land around you into cropland, you begin to generate enormous food surpluses, which have to be protected from the elements and from other creatures--including other people. Ultimately they have to be locked up. Though it surely isn't recognized at the time, locking up the food spells the end of tribalism and beginning of the hierarchal life we call civilization.

"As soon as the storehouse appears, someone must step forward to guard it, and this custodian needs assistants, who depend on him entirely, since they no longer earn a living as farmers. In a single stroke, a figure of power appears on the scene to control the community's wealth, surrounded by a cadre of loyal vassals, ready to evolve into a ruling class of royals and nobles.

"This doesn't happen among part-time farmers or among hunter-gatherers (who have no surpluses to lock up). It happens only among people who derive their entire living from agriculture--people like the Maya, the Olmec, the Hohokam, and so on."

I bet if I asked most people if they like their job most would say no. In fact, I wouldn't be afraid to say that over 90% would say no. But then if I tried to explain to them why they have to work from what I just quoted out of Quinn's Beyond Civilization they would probably think I'm speaking a different language. I mean that's what most people go to work for is to put the "locked up" food on the table, right? Why aren't more people who hate there jobs trying to unlock the food? Are these the right questions to ask?...Hmmmn

1.Civilization

2. Agriculture

3. Jobs

4. Labor

"Making food a commodity to be owned was one of the great innovations of our culture. No other culture in history has ever put food under lock and key--and putting it there is the cornerstone of our economy, for if the food wasn't under lock and key, who would work?"

He than goes on to say...

"People don't plant crops because it's less work, they plant crops because they want to settle down and live in one place. An area that is only foraged doesn't yield enough human food to sustain a permanant settlement. To build a village, you must grow crops--and this is what most aboriginal villagers grow: some crops. They don't grow all their food. They don't need to.

"Once you begin turning all the land around you into cropland, you begin to generate enormous food surpluses, which have to be protected from the elements and from other creatures--including other people. Ultimately they have to be locked up. Though it surely isn't recognized at the time, locking up the food spells the end of tribalism and beginning of the hierarchal life we call civilization.

"As soon as the storehouse appears, someone must step forward to guard it, and this custodian needs assistants, who depend on him entirely, since they no longer earn a living as farmers. In a single stroke, a figure of power appears on the scene to control the community's wealth, surrounded by a cadre of loyal vassals, ready to evolve into a ruling class of royals and nobles.

"This doesn't happen among part-time farmers or among hunter-gatherers (who have no surpluses to lock up). It happens only among people who derive their entire living from agriculture--people like the Maya, the Olmec, the Hohokam, and so on."

I bet if I asked most people if they like their job most would say no. In fact, I wouldn't be afraid to say that over 90% would say no. But then if I tried to explain to them why they have to work from what I just quoted out of Quinn's Beyond Civilization they would probably think I'm speaking a different language. I mean that's what most people go to work for is to put the "locked up" food on the table, right? Why aren't more people who hate there jobs trying to unlock the food? Are these the right questions to ask?...Hmmmn

1.Civilization

2. Agriculture

3. Jobs

4. Labor

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)